Do children and young people grieve differently?

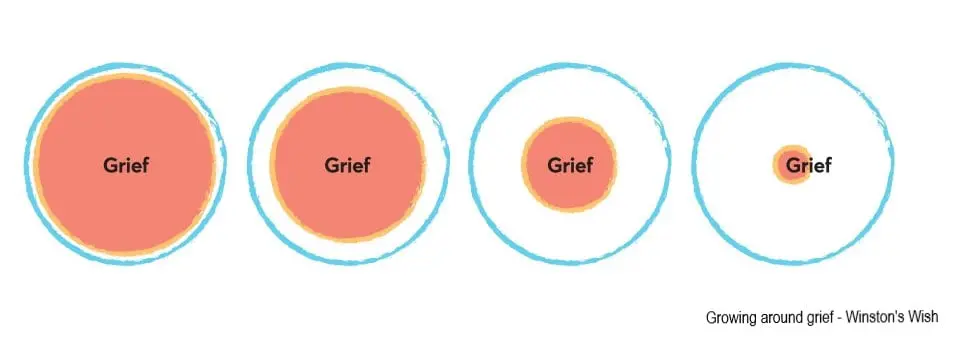

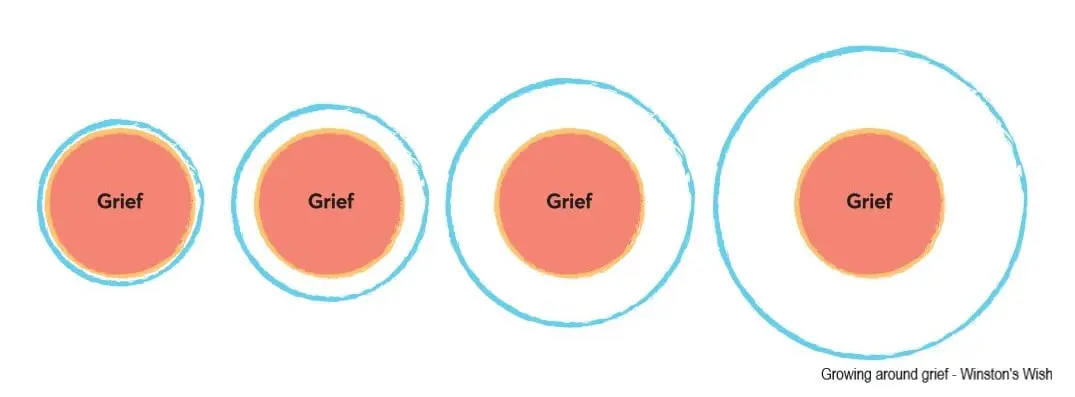

Often, people will talk about the ‘different stages of grief,’ suggesting that everyone’s grief follows the same path through the stages of grief and that their grief will get smaller over time. We know from our experience that it’s not that simple and we prefer to look at it another way, the idea of ‘growing around grief.’

Growing around grief

You’ll have heard people say something like ‘time heals,’ suggesting that grief gets smaller. However, bereaved people’s experiences suggest that, actually, grief doesn’t go way, it doesn’t even grow smaller – we grow larger around it.

This way of looking at grieving was developed by Lois Tonkin.

To begin with, grief feels as if it takes up everything and there’s no room inside us for anything else. Earlier models of grief suggest that over time grief grows smaller.

In fact, our grief stays the same size but in time we grow around the grief, so we have space for other thoughts, experiences and emotions.

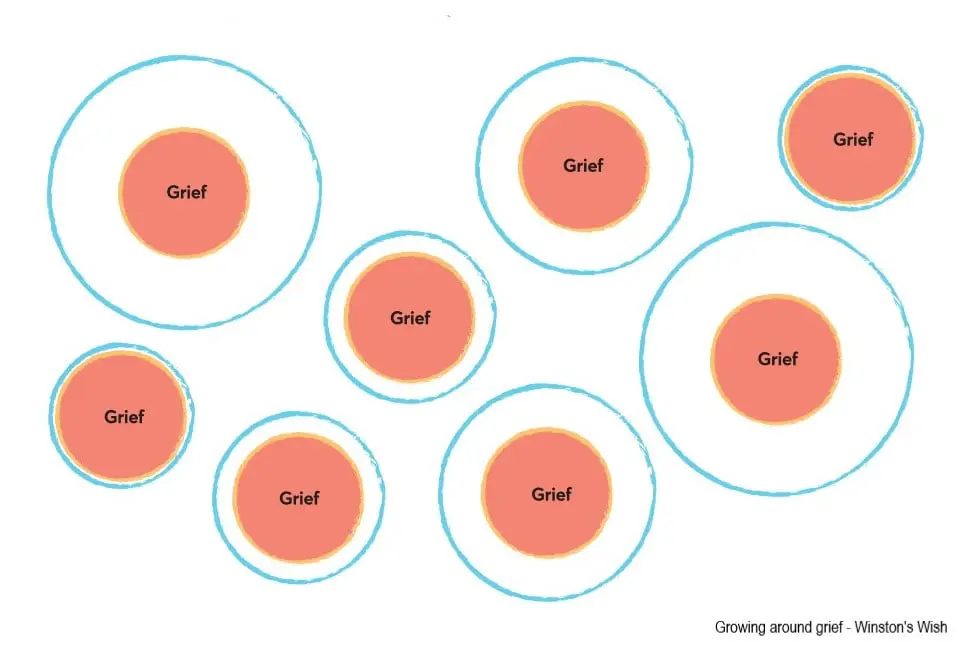

This isn’t a straightforward linear process. Some days, grief takes up all the space and some days you have room for other feelings and experiences. Over time, these may become more frequent. But the grief hasn’t shrunk – you’ve grown round the grief.

Do children grieve differently to adults?

Although they will feel it just as deeply, children will experience and express grief in different ways to adults. The way children grieve will mostly depend on their age and understanding of death as well as their ability to talk about their thoughts and feelings.

This can often make their reactions appear quite different in comparison to how adults may express their feelings. Initial reactions to the news of a death may vary greatly from considerable distress, to finding it hard to speak, or they may not react very much at all.

Whilst this can be difficult for adults to understand and to keep up with, it is very normal, and it doesn’t mean that the child doesn’t care or isn’t impacted by what has happened. It may take them some time to process what has happened and they might need some help in finding ways to express how it feels for them.

Adults can often feel overwhelmed by grief, as if they are caught in the current of a river and find it hard to get out. Whereas young children especially, tend to ‘jump’ in and out of their grief – a little like jumping in and out of a puddle.

What is puddle jumping?

There is no linear journey of grief, bereaved children and young people can experience different thought and feelings at different times. In fact, children often jump in and out of their grief – we call this ‘puddle jumping.’

In the process of growing around their grief children might appear to move in and out of their grief feelings quite frequently and quickly. This is very normal and is the way young people process grief.

Children, particularly young children, may jump from feeling very upset and distressed one moment to wanting to know what’s for tea or whether they can play football, for example, the next. The reason for this is that children need a break from the powerful emotions that accompany their grief and so are able to jump out of them for a while in order that they are not overwhelmed.

This can be very confusing for children, and at time the adults around them. Although they will need time and understanding to help them to process their loss, with clear information and support young people will be able to grow around their grief.

How much do children understand about death?

How much children understand about death will be different at different ages and stages of development. These are the most common understandings of death by children of different ages but remember that all children are special and unique and therefore, they will respond to and understand death in their own special and unique way.

Children under the age of five will not understand the finality of death. Very young children often think that death is reversible and that their person who died can come back. That’s why it’s important to use clear and simple language like ‘dead’ and ‘died’. At this age, children have a very literal understanding so, if we say, “we’ve lost Granny”, children under five will think “where can we find her?”

Young children won’t understand the difference between dead and alive unless we show them – maybe you could go out into the garden, find some dead and alive bugs and compare them together.

It’s important to give clear and concise information, answer young children’s questions and make sure that they have understood what you say. It is not uncommon for young children to repeat the story of the death or ask lots of repetitive questions – this doesn’t mean they haven’t listened or that you haven’t explained it well enough, this is just how they work out what’s going on.

Some common reactions within babies and very young children include:

- Trouble with sleeping and eating

- Crying, sometimes inconsolably

- Become more withdrawn or more clingy

Children who are aged 5-8 are starting to understand that death is something that is final, however, this can feel spooky or frightening. It might help to use books that explain death and the life cycle as a natural, normal thing – you’ll find our reading list here.

At this age, children are starting to think about themselves and how that fits with the death – what is called ‘magical thinking’. For example, they might think that it’s their fault that the person has died – “I didn’t eat my breakfast and therefore mummy has died.” It’s important to give them clear information about the death and to help them understand that it’s not their fault.

Children aged 5-8 will be beginning to think and feel strong emotions but they won’t have the vocabulary to understand theme or to explain them to us. You can help them to understand that the funny feeling in their tummy might be called ‘worry,’ or that clenching of their fists and gritting of their teeth might be called ‘angry.’

Some common reactions within this age group include but are not limited to:

- Increased anger and tantrums – often linked with anxiety

- May be more clingy

- They may become more withdrawn or anxious

- Reverting to behaviours they had when they were younger e.g. bedwetting, thumb sucking

- May ask the same question repeatedly and need reassurance that the death was not their fault

At this age, children understand the finality of death and that the person is not coming back. They are also more aware of the impact the death has on them, for example, that special person won’t be there for important birthdays or milestones like moving to secondary school.

By this age, children will have developed a vocabulary to understand their thoughts and feelings, however, they might not want to share them for fear of upsetting other people. Not sharing their feelings often leads to big emotional releases such as anger or distress. You can help them by giving them permission to talk about how they feel about the person who has died and to talk about their worries and concerns with you.

Children who are aged 9-12 are entering a time of transition and are likely to be moving to a new school. Transitioning from one school into another can be very difficult for some children who have experienced a bereavement. You can help them by listening to their worries and concerns and maybe by talking to the new school to let them know about the bereavement.

Some common reactions within this age group include but are not limited to:

- Complaints of somatic symptoms such as a sore tummy or headache

- They may retreat into themselves

- Show increased aggression

- Develop a curiosity around death and/or worry that others might die too

- May have growing concerns around feeling different from their peers

- Some children may also find ways to blame themselves for the death, and at this age they may do ‘magical thinking’ where they think they did/said/thought something that caused the death

Teenagers have an adult understanding of death and dying and are much more aware of the finality of death. They also understand what will mean for them and their lives, both now and in the long term.

At this age, young people are starting to question the meaning of life and the afterlife and the death of someone important can cause them to reflect more on this or consider ‘what’s the point?’

It’s important to give teenagers clear and honest information about the death and to answer their questions. Young people can look at things on the internet about the death and some of this may be unhelpful – you should be their source of truth and clarity.

Young people can end up looking after or caring for their parents or siblings after the death of somebody. They can worry about losing control of their emotions and need support to explore these. They might find it easier to talk to another trusted adult – help them find someone they can open up to.

Some common reactions you may see:

- Intense feelings of sadness, guilt, anger

- Feeling worse about themselves

- Become withdrawn or finding it difficult to talk about their feelings

- Engage in risk-taking behaviours and test boundaries

- Worries around their own health

- They may start to ask questions around the meaning of life: What’s the point? Why did this happen to them?

What is important is to remain available for grieving teenagers, but not to push. Remind them that you’re there if and when they need, while maintaining the limits that you would normally have in place.

How does a child’s grief change as they get older?

Feelings of grief may affect children differently at different times in their lives. As children and young people grow, they may have different questions or experience different emotions in relation to their developmental stage and understanding of what it means for them. They may revisit their grief on special dates or anniversaries or at significant milestones, such as when they change schools, go to university, get married, or have children of their own. It can sometimes help to be prepared that these days or times might be harder, and to find ways to remember the person who has died and to take extra care of yourselves.

Sometimes children and young people can struggle a bit more with their grief as they get older. Their needs may change, and sometimes they might feel as if they didn’t grieve when they were younger and the grief needs recognising in a different way now. It’s useful to know that they haven’t ‘grieved wrong’ or ‘not grieved,’ but that as they grow older their ‘grief needs’ change. Validating how a young person is feeling and acknowledging that it’s okay for their feelings to change can be some of the most useful things to do and say when supporting someone as they grow up.

Ways to support grieving children and young people:

Be understanding

It is important to show understanding for both grieving styles, whether you’re in or out of the river or puddle. You should be able to express your grief, and children need to be able to express their grief when they need to, as well as play when they need to.

Express your own feelings

Children look to adults to learn how to express their emotions and feelings. So, if you are able to put into words, ‘I’m feeling particularly sad or angry today because I miss them’, then this can help give children the words and permission to do the same.

Although children may initially be upset when they see you cry, it can actually be very helpful for them if you are able to give them an explanation. Something along the lines of ‘there’s nothing you have done that has upset me. I’m crying because I’m sad that Daddy died’. You can further this explanation by saying that ‘these tears and this sadness are already inside me, and it’s really good to let some of them out so that I don’t have to hold it all inside.’

Let them know it’s okay to talk

It can be helpful to let the child know that you are happy to talk with them about their person whenever they want to and to let the child know if you’ve noticed if they seemed particularly quiet or restless that day, and to check in if they want to talk about the person who has died.

How to get bereavement support

Winston’s Wish provides support to grieving children, young people and their families all over the UK, and we are here for you if you need us.

Our team of bereavement specialists are available to speak with right away. No appointments or waiting lists, just real-life grief support. Call us on 08088 020 021 (open 8am-8pm, weekdays), email ask@winstonswish.org, use our online chat (open 8am-8pm, weekdays) or text or WhatsApp us on 07418 341 800 (open 8am-8pm, weekdays). You must be 13 or older to receive support via WhatsApp.

For urgent support in a crisis, please call 999.

Connect with us

Sign up to our newsletter and follow us on social media for all our latest news and advice on supporting grieving children and young people.