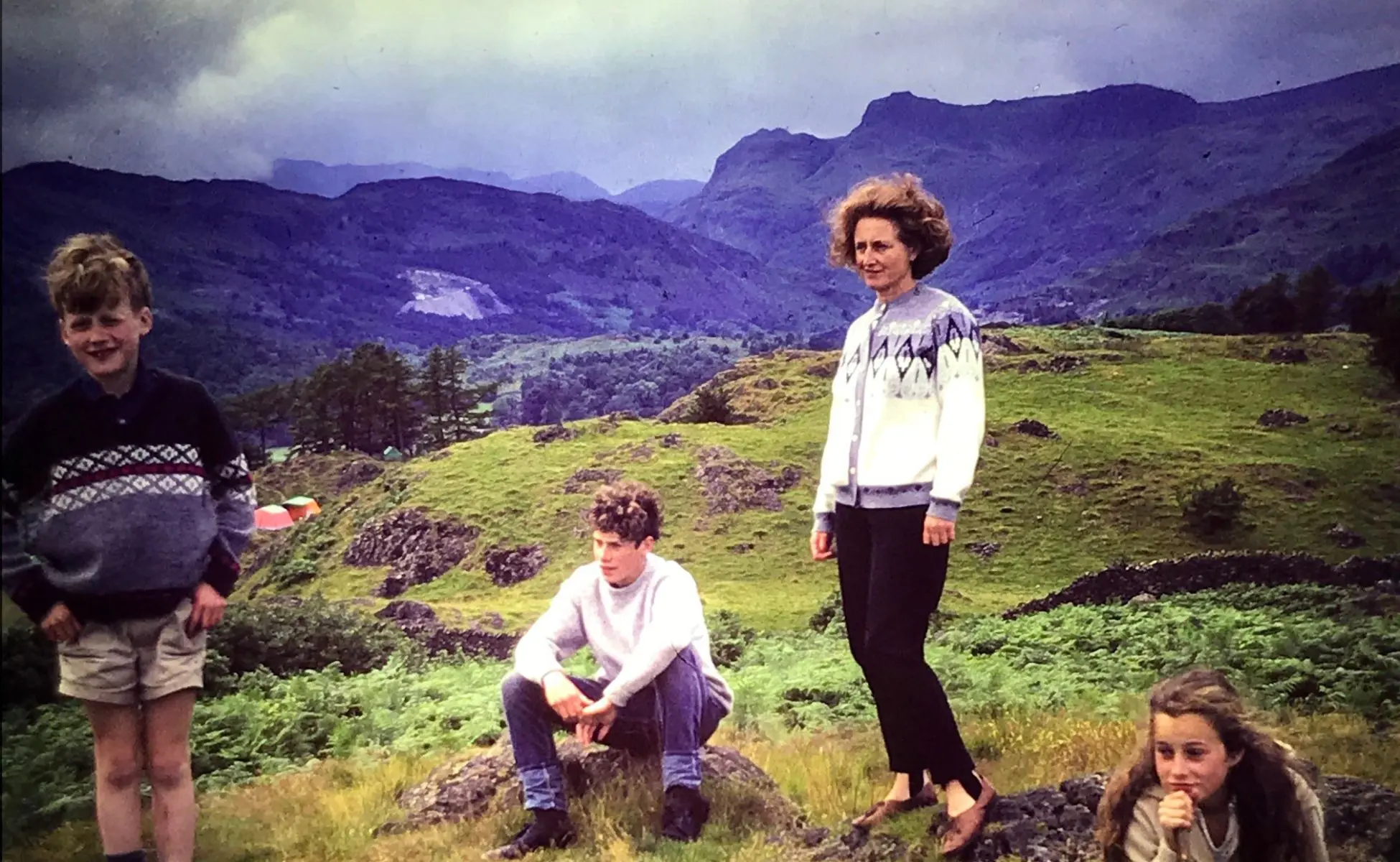

Written by Winston’s Wish supporter, Nick

It was nearly 47 years ago, as a 19-year-old, when my life was turned upside down.

At around 4 am, a knock on my door, and two oversized policemen squeezed into my room. After suggesting I sit down, they told me, without much further softening of what was to come, that my parents had died in a car crash.

Grief is a difficult term to understand, it covers so much: denial, shock, loss, loneliness, anger, and managing other peoples’ reactions.

When I was told this at 4 am, I think I just glazed over; of course, you don’t believe it, this can’t really be happening? So, my immediate reaction may have been one of blankness, which the police interpreted as that I was taking it very well, so they left.

As I look back, it’s hard not to feel anger at having to blunder, over decades, through these stages. It is wonderful that organisations like Winston’s Wish are there now to help and support young people through parental loss and grief.

I was at university at the time and received no support, and my method of getting through all this was strongly, and badly, affected by having to manage other people’s expectations. In the 1970s, this was very much a time when you were expected not to show emotion, bottle things up, and ‘carry on’.

As I made my way home, alone, later that day, there was a newspaper billboard outside the rail station. It said, ‘Leeds couple dead in A61 crash.’

I remember distinctly thinking, are they talking about my mum and dad? It was only when I returned home and saw my elder brother and sister there with their partners and children, that the loss hit me.

Straight after the funeral, the first signs of having to deal with other peoples’ reactions became evident, when an uncle said I should call him if there was anything I needed and handed me his business card! Needless to say, I never spoke to him again.

The future weeks, months and years to come…

After two weeks I returned to university. Although I would have wanted someone to talk to, the reaction of other people became something that I had to learn to manage. At the time the way to do that seemed to try to block out my parent’s death. That worked during the day, but not at night when trying to sleep.

If I could speak to them now, I would tell them that I miss them, but that things worked out OK.

Initially, I could see people’s embarrassment when they first met me on return, as, understandably, they didn’t know how to deal with me. It became clear very quickly that if I was asked how I was, a simple “OK” was preferred to any attempt to say how I felt.

Over the next 15 – 20 years or so, if the conversation seemed to be moving on to general parent chat (where they lived, what did they do, etc.) I soon realised that if I couldn’t subtly change the subject, I would find an excuse to leave the group, at least for a few minutes for the conversation to move on.

My siblings lived quite some way away and had families of their own, so were distracted and busy with their lives. During university holidays, I always tried to hang around for as long as I could, trying to deflect questions about why I didn’t go home. All I wanted to say, but couldn’t, was that I didn’t have one.

Alongside this was the absolute fear of losing anyone close to me. If there was a knock at the door or a phone call, any later than, say 10 pm, I would just freeze, and my heart rate would surge fearing the worst. It also meant that I resisted ever getting too emotionally close to girlfriends. On a few occasions when this happened, it would hit me like a bullet that I had crossed this line, I typically would just cry myself to sleep at night fearing that there was now someone else I couldn’t bear losing.

As time has gone on, I look back now with feelings of sadness, sometimes anger, that I missed out on knowing my parents as an adult and understanding them much more.

I’m happily married with a family, retired having had a successful career, but there is always that part that wonders what would be different if I had received the right support.

In those days following the funeral, I simply had to get on with life, largely on my own, and there wasn’t any organisation like Winston’s Wish around when I needed them.

I now support Winston’s Wish with a monthly donation so that no child or young person in that situation has to face their grief alone and ‘just get on with life.’

How to get grief support

Winston’s Wish provides support for children, young people up to the age of 25 and adults supporting them.

You can call our Freephone Helpline on 08088 020 021 (8am-8pm, Monday to Friday), email us on ask@winstonswish.org or use our live chat (open 8am-8pm, Monday to Friday). Our support workers are here to listen, can offer immediate guidance and resources and tell you what support we can offer and what might be most suitable for you.

Our Winston’s Wish Crisis Messenger is available 24/7 for urgent support in a crisis. Text WW to 85258.

Make a donation today

By giving regularly like Nick, you’ll be helping more children and young people have access to support through their grief.

Please ensure that your browser version is up to date and that you do not have any extensions which prevent pops ups, so that your donation can be processed by our payment system. Thank you.